“After 1670, the Acadians were much more free-ranging in settlement, no longer depending on the seigneurial system.”

These words come from Chignecto & Remsheg prior to 1755: Mi’kmaq, Acadians, French by Stephen G. Leahey.

The image of free-ranging Acadian ancestors seems at odds with the idea of settled dyke-building, agrarian people living in hamlets of relatives.

The term reminds me of the way these words landed in the brain of a friend’s granddaughter. As a tween Abby (à Tony à Judith) placed several eggs from a carton marked “free-range” on the floor and waited. When Judy asked what she was doing, Abby said she wanted to see eggs range freely.

That some of our Acadian ancestors moved around a lot and that they weren’t a monolith of settled souls living idyllic lives, planting and harvesting by day, and fiddling and smoking clay pipes by evening isn’t really news. But how much free ranging did they actually do? And who was doing it? And why? And when?

For example, when Jacques Bourgeois left wife Jeanne Trahan in Port Royal in 1671 while he and their two eldest, Charles and Germain, headed up to the Isthmus of Chignecto to found the Bourgeois colony, did Jeanne think “Oh, there goes my husband, free-ranging again while I wait it out here”?

Or was she more of a mind to think “Thank goodness they’re looking for a new place because I’m tired of the way this one keeps going back and forth between the French and the British. I’ve had it with pirates and looting. I’m sick of cleaning up all the soot and smoke from those guys torching our homes”?

The question “why leave home?” gnaws at me.

Once upon a time, in a Paris cab en route to the airport, I asked my brother John why he thought our ancestors left Paris. “For a better life,” he said. “Or because they were explorers.”

“That’s not enough of a reason,” I said, “to uproot your family, some of them toddlers, get on a ship that’s going to bob about for two months in storms and wayward currents, at the end of which you’re eating wormy meal. Or, if you’re a single woman, to leave for a life with a stranger in a strange land. What else was going on?”

He looked like a deer in a headlight. My brothers often do when I try to engage them in speculations on what motivates people to do what they do. Especially family members.

Why hadn’t the story of Acadian migrations come up in school history classes? Sure, we heard a bit about the French: La Salle and the Mississippi River, the British win on the Plains of Abraham, and Lafayette coming to help the rebelling colonies.

But the migration of Acadian people? Practically anyone else’s migrations, forced or voluntary, got at least a passing mention: Pilgrims, enslaved peoples, Chinese railroad workers, Scandinavians to the prairies, Italians and Polish immigrants at Ellis Island, Irish escaping a potato famine.

But not a word about Acadians. Heck, I didn’t even hear about Evangeline until I was an adult poking around in the world of poetry.

It’s not like there aren’t a lot of us.

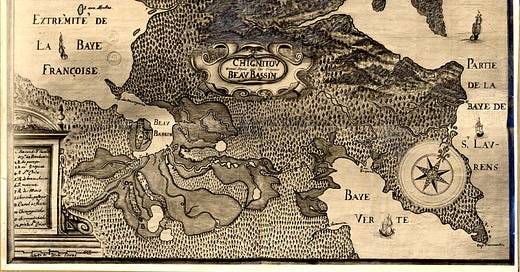

ameriquefrancaise photo

The idea came to me that maybe if I followed around one group of Acadian family ancestors, I might glimpse how forces from the outer world — what we call history and politics — intersected with the inner worlds of their selves and their relationships with each other. Maybe if I watched them range freely, I could understand some part of how they felt about their lives and why they went where they went when they did.

If I’d started with one of my Bourgeois lot, I knew I’d quickly get into the weeds of Acadian endogamy. So, I picked a paternal line that began — or ended, depending on how committed a person is to identifying heritage through male names — with a Vigneault daughter. Start with a less common Acadian name. Start with Marie Vigneault.

Easy, right? Just look at where she was born, married, and died. Born about 1740 in Beaubassin, married in 1764 in St.Pierre-et-Miquelon, died in Nicolet, Quebec in 1819. Not a lot of ranging about, heh?

That’s like looking at an unopened carton of free-range eggs. You know they came from a hen somewhere, but the details just aren’t there. You just don’t know much about any one hen’s life or progeny looking at those crated orbs.

And so it is with Marie, and probably most ancestral Acadian women.

Two years into this, reading umpteen history books with occasional mentions of a male Vigneault family member; scanning census records from Port Royal, Port Toulouse, and Beaubassin; and reading records from the Massachusetts Archives, I have a glimmer of Marie’s life and where she ranged before her mid-20s.

Ai-yai-yai.

This ordinary young woman likely lived on the wrong side of the Missaguash River in the years before the Big Upheaval. Circa 1750, when she was 10, the French and Mi’kmaq alliance burned homes on the south side of the river in English Acadie.

Marie became a refugee on the north side in French Acadie. At age 12, she and her family are at Port Toulouse where one of her uncles (Joseph) lived and where her dad (Jean-Baptiste) grew up.

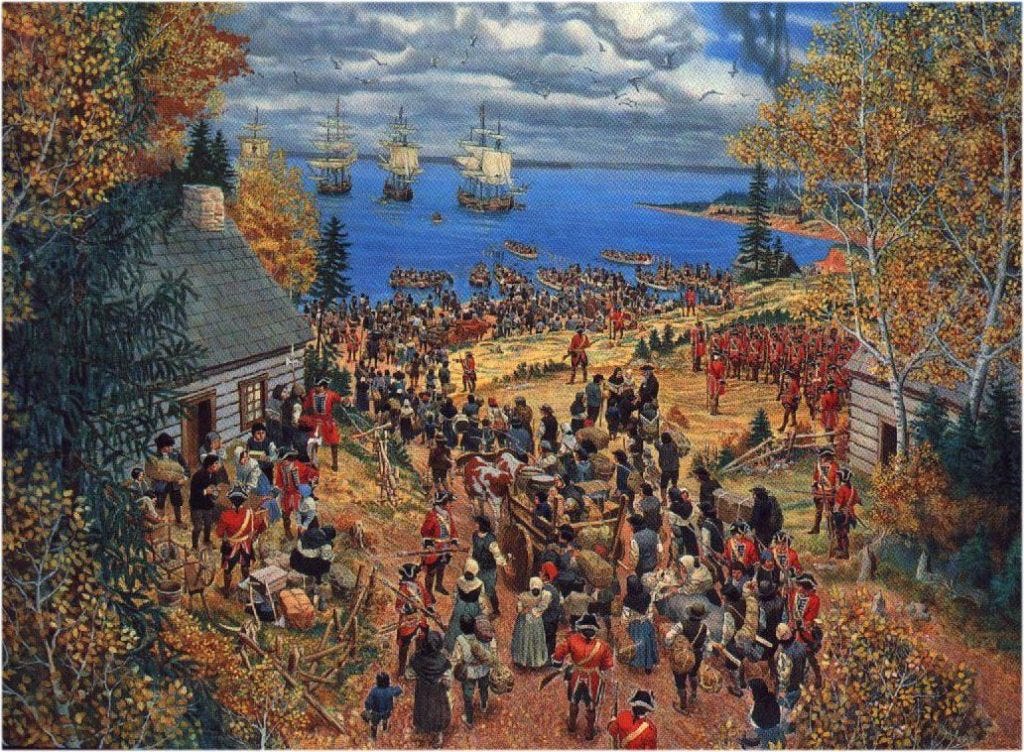

During the next few years, she returned to the Chignecto isthmus to Baie Verte from where, in 1755, at age 15, she was loaded with her Vigneault relatives onto the schooner Jolly Phillip en route to Georgia.

La déportation des Acadiens en 1755. Photo: Musée acadien de l'Université de Moncton https://l-express.ca/deportation-des-acadiens-la-liste-de-winslow-expliquee/

The story goes that the British sent the Acadians they considered the most dangerous to Georgia. Probably Marie’s Uncle Jacques was among those so considered, and the reason the Vigneaults were sent to that southernmost British colony.

At least this extended family stayed together, which wasn’t always true during the deportation. Except for Marie’s younger sister Marie Theotiste, who somehow ended up in Quebec City, where she died of smallpox.

I can only imagine that, by the time they reached Georgia, Mama Vigneault, aka Agnes-Anne Poirier, was exhausted. And that Marie, now age 16, struggled to make sense of moving around after one home after another was burned by people she might have considered friends or neighbors. How did they endure? I tried to imagine how they might wrestle with a moment of despair (Her Mother’s Daughter).

In Spring 1756, from Georgia, like some 18th-century Moses, Uncle Jacques led a flotilla of rickety boats carrying about 100 extended family members up the East Coast. Destination: Acadie.

Uncle Jacques may have been a “silver-tongued devil” as one historian called him. Or maybe the governors of the colonies didn’t want French Catholic immigrants living among them. Wherever the Vigneault flotilla put in, the colonial governors were more than happy to give them a pass to move on.

Until they reached Massachusetts.

By then, Gov. Charles Lawrence in Nova Scotia, the man responsible for the deportation, had sent a message to Massachusetts Governor William Shirley that no way, no how, was he to let those Acadians return to Nova Scotia. Split them up and keep them away from the coast. Those guys know too much about sailing.

Marie and her family landed in Sandwich/Bourne where local officials brought them food and necessities until the sheriff showed up to remove them. These Vigneaults were stuck in Massachusetts until 1763 when the Seven Years War (the French and Indian War) ended.

From Massachusetts, Marie went to St. Pierre-et-Miquelon, where she got a break long enough to marry. She was 24.

During 14 years from age 10 to 24, she watched her village burn at least twice, was a refugee at the hands of combatants on both sides of a war, traveled down the East Coast of colonial America in a schooner then up the coast in rickety watercraft, lived among English-speaking Protestants who may or may not have tolerated her and her family, then migrated to the one island group France claimed when it relinquished its claim to Canada to Great Britain.

Politics, war, youth, family ties — all played a role in her travels. Marie was about as freely ranging as the eggs in Abby’s carton. Her travels were not for adventure, exploration, or a better life.

And this is between “she was born” and “she married.” I have yet to follow her around from St.Pierre-et-Miquelon until she settles in Nicolet, Quebec.

Lineage

Ann (Acadiann) à H. Wilfred Forcier à Angelina Chenevert à Ulderic Chenevert à Marie-Louise Belisle (Chevrefils) à Marguerite Benoit à Marie Victoire Bourgeois à Marie Vigneault à Jean-Baptiste Vigneault à Maurice Vigneault (and Marguerite Comeau)

Maurice Vigneault, though he came from Quebec, had ties to relatives in Acadia. His father Paul, a soldier in Quebec, was the nephew of Marie Catherine Vigneault, a French Pioneer of Acadie

Resources

1752 Census of Ile Royale (Cape Breton)

Acadian census lists and links

Prior to the influence of Longfellow's poem, historians generally focused on the founding of Halifax (1749) as the beginning of Nova Scotian history. Longfellow's poem shed light on the 150 years of Acadian settlement that preceded the establishment of Halifax. In: McKay, Ian; Bates, Robin (2010). In the Province of History: The Making of the Public Past in Twentieth-Century Nova Scotia. McGill-Queen's University Press. ISBN 978-0-7735-3703-3. JSTOR j.ctt81b7b.

I love this! I always try to find out what the driving force was behind ancestors moving as well. I want to know why! Because I can't imagine getting on one of those rickety boats voluntarily 😅

Jacques Bourgeois and Jeanne Trahan are my tenth great grandparents. But I'm apparently descended from them 47 ways. Endogamy indeed 🤣🤣

Fascinating! I loved this account of one deportee, that brought this terrible event to life, and showed us what incredible courage and endurance she and her fellow victims of the Derangement had. In answer to your question as to why a French person would choose to settle in New France in the seventeenth century, I can tell you as a European historian that the timeframe for French migration to Canada was short compared to most national migrations to the new world, with most people arriving in a window of about 60 years. This migration coincided with the terrible hardship of the Little Ice Age- what Annales historian Pierre Goubert called the "tragic seventeenth century." France experienced famines over and over again-- with harvest failures in 1630-1631, 1649-1652, 1661-1662, 1693-1694, and 1709-1710. Of course the people who came to Canada were not starving peasants, but the general political, social and economic crisis conditions would be enough to make anyone want to start fresh somewhere else. And of course, there were some nice incentives from the government to do so!