Which is worse: remembering trauma, or forgetting it?

Elizabeth Rosner, Survivor Cafe

At this point on a calendar cycle, 269 years ago, the Vigneaults and other families (paternal names: Bourg, Hebert, Cyr, Bourgeois, Girouard) have sailed down the Eastern seaboard of the now-U.S. on the schooner the Jolly Phillip under ship’s captain John Waite. They were deported in October 1755 from Beaubassin (Sackville, New Brunswick).

They were among those the British considered the most troublesome so they were sent from what was then, for all intents and purposes, the 14th Anglo-American colony (Nova Scotia) to the furthest southern one of Georgia.

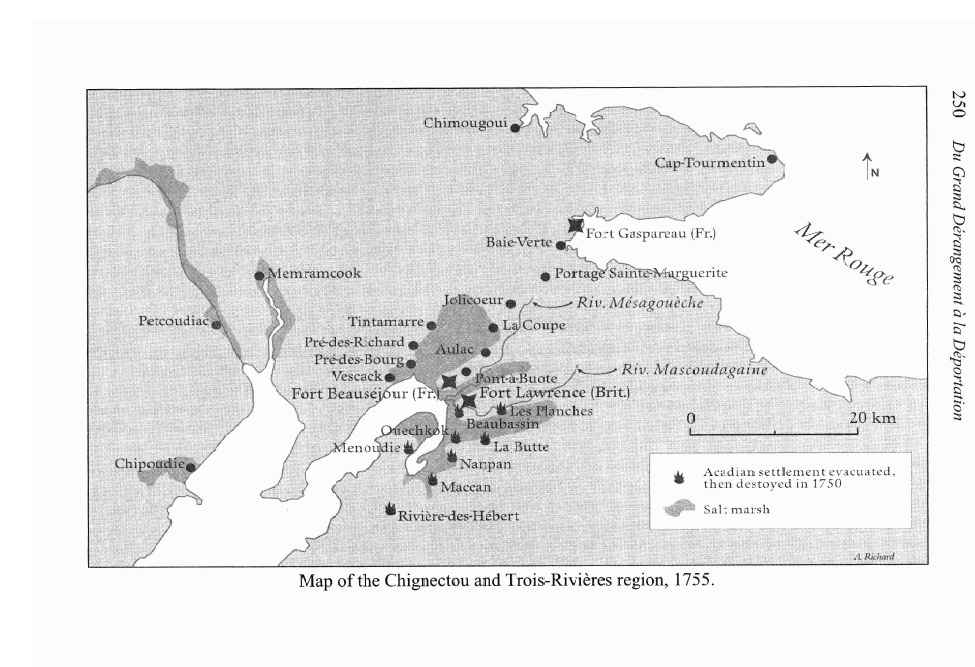

Part of what made these Acadians troublesome was that, though they were Acadian men or descendants of Acadian men who signed conditional oaths of allegiance to the British kings before 1755, they had moved from English-held Acadie to French-held Acadie. They were the “Deserted French inhabitants” (see Paul Delaney in resources).

“Moved” is a euphemism; it fails to capture the reality of the experience. It was hardly the “oh, let’s go join French Acadie because we’re treasonous rebels” that British General Charles Lawrence claimed it was.

Acadian homes on the English side of the Missaguash River were burnt in 1750 under French orders executed by French and Mi’kmaq allies. The Vigneaults “moved” in with relatives whose homes and lands were yet intact on the French side of the river. Several Vigneaults ended up in Port Toulouse (St. Peter’s, Cape Breton) as refugees, and then back in Baie Verte (NB) by deportation time.

That’s a lot of rootlessness in the life of the particular person I’m following: Marie Vigneault. From age 10 to 15, she lived hither and yon in a land claimed by French and English monarchs. A land that belonged to the Mi'kmaq. At age 15, her latest home destroyed, she boarded a schooner going to lord-knows-where. She was a “Deserted French Inhabitant” having had no say in her residence by virtue of her age, sex, and consequences of military actions.

To make matters worse, the night before the Jolly Phillip had headed out, British troops — probably including New England colonials — robbed the passengers of “a great deal of money and many clothes” (see Delaney, p. 261).

Trauma, after trauma, after trauma.

Because they were “other” to the British and Bostonnais.

Better to remember or forget?

If the answer is “forget,” then why learn any history at all?

If the answer is “remember,” then how to do that without getting stuck in misery?

How do you reconcile that, but for a few hundred years, this could have been you or me?

But for a few thousand miles of geography now, it could be you or me in Ukraine or Gaza.

Or the experience could be closer in both time and space.

Though it is not an experience of mine, many cousins tell family stories of prejudice and outright violence because of their minority status as French Catholics through time.

Which reminds me of those told during The Rassemblement of August 1991.

In a moment of then uncharacteristic boldness, I’d asked the organizer whether I could come though I wasn’t from Maine or an alumni of the University of Maine.

Sure, of course, the more the merrier.

At this gathering of Franco artists, the distress these creatives expressed about the ongoing harm they felt by Anglo culture gobsmacked me. Stories of the KKK coming to their parents’ or grandparents’ homes and burning crosses on their lawns. Anger and hatred. Impaired sense of pride in heritage.

I asked Yvon Labbé (Director of the Franco-American Centre) how could it be that so many weren’t proud of being French, that they complained instead about their status and the way they were treated.

Thankfully, he had a wisdom that saw through my naiveté.

He told me about fruit: Ah, Ann, you have to squeeze lemons before you can make lemonade.

I never forgot, and have appropriated and shared it.

Complaining = squeezing lemons.

The first lesson of cultural trauma recovery, then, is complain about it. In a contained environment with other people who know what you’re talking about. With someone who can hold space for empathetic witnessing with the expectation that there is sweetness at the end. But bitterness first. Get all the juice out of those lemons.

And grieve the losses for the ancestors who couldn’t.

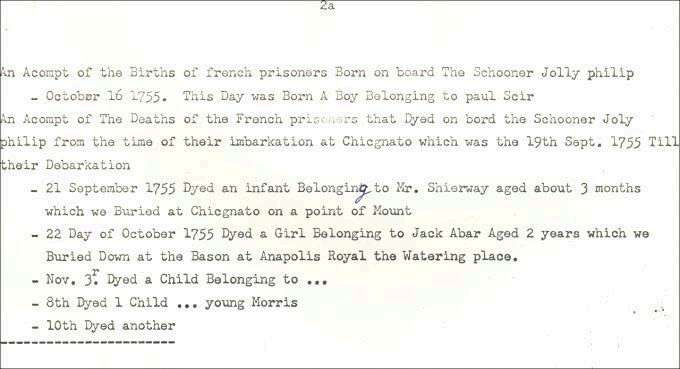

Like the children who died on the Jolly Phillip.

from John Waite’s ship’s log

In a few weeks, on December 13, New Brunswick will commemorate the Acadian losses. On that day, you can visit Descendants of Michel Hache dit Gallant and other Acadians where administrator Nicole Gallant Nunes will release the first of her Memorial list of Acadians who died due to the Expulsion. Hold vigil with them on that Acadian Remembrance Day.

Thank you to Patrick Lacroix and Steve Riel for identifying the year of that Rassemblement.

Resources

Paul Delaney, "The Acadians Deported from Chignectou to 'Les Carolines' in 1755 : Their Origins, Identities and Subsequent Movements". In Du Grand Dérangement à la Déportation. Nouvelles perspectives historiques, edited by Ronnie-Gilles LeBlanc (Moncton, Chaire d’études acadiennes, 2005) pp. 247-289.

Too many more recent traumas are diminished or ignored. And so many people continue to say "that was a long time ago, get over it" when the victims were not allowed to voice their trauma, or seek apologies or restitution.

I had thought that the inhabitants of Beaubassin had all evacuated to Fort Beauséjour when the settlement was torched. I didn't know that some simply moved across the river.

Such a terrible time for them. Thank you for telling this story.