Acadian bits and pieces, part 2

What about godparents?

Tell all the truth but tell it slant —

Emily Dickinson, 1868

Telling the truth slant dovetails well with what I think of as slant research — learning about someone’s life by looking at the bits and pieces that are documented about those with whom a person lived or was related to during the lifetime.

I’m digging slant to my 5th great-grandmother Marie Vigneau by looking a bit more into her Uncle Jacques’s life. I’ve selected two suggestions from historian Lisa Maguire’s microhistory writing model: reading against the grain and looking for the scattered traces.

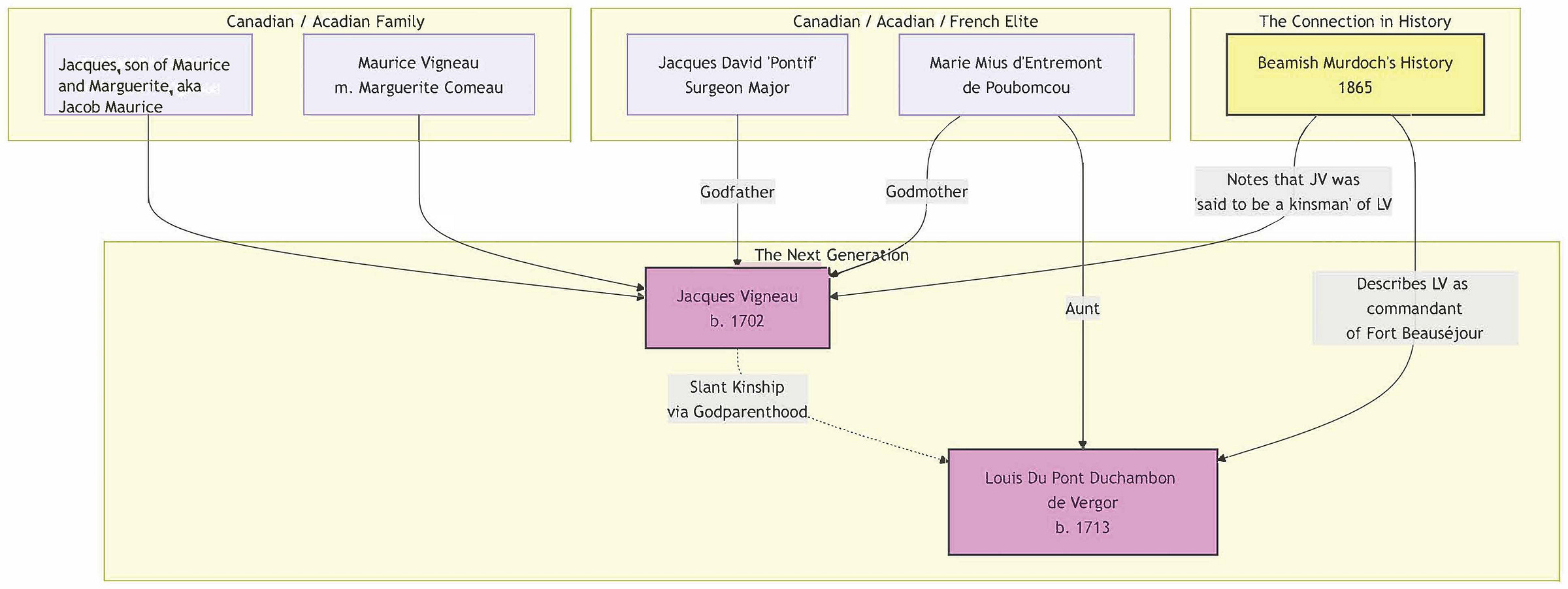

Chart courtesy of historian Lisa Maguire

The history I’m reading slant is Beamish Murdoch’s 1865 A history of Nova Scotia, or, Acadie. In his description of the events of summer 1755 in Beaubassin, he writes what seems to me an off-hand comment about Jacques’s family ties:

Jacob Maurice, who is said to be a kinsman of M. Vergor, came in also with some habitants of baie Verte, to make terms. (p. 273)

Jacob Maurice is Jacques Vigneau’s name in English. The terms were for the surrender from the French to the British of Fort Gasperaux, which fell after Fort Beauséjour.

The came in also follows the remark that Joseph Brossart called Beausoleil, came in under a safe conduct to propose a peace with the Indians, praying pardon for himself. No mention was made of Brossart’s kinships. Something about Jacques’s ties to Vergor mattered, even as Murdoch wrote about the surrender.

Who was Vergor and how were he and the Vigneaus kin?

Vergor was the French commandant of Beauséjour when he surrenderd the fort to British Lieutenant-General Robert Monckton on June 4. Vergor’s full name was Louis Du Pont Duchambon de Vergor.

According to some historians writing in English, Vergor was a human being of questionable morals and incompetent leadership.

Well, not every family member is going to shine.

Murdoch noted that Vergor had a lot of relatives in Acadie (pp. 234-5). Given the many ways in which families were intertwined in 1755 Beaubassin, that conclusion didn’t require much deduction.

Still, how in particular were Jacques Vigneau (b. 1702, Port Royal, NS) and Vergor (b.1713, Sérignac, Saintonge, France) kinsmen? What was their cousinage?

Murdoch says Vergor’s parents were Acadian Jeanne Muis d’Entremont du Poubumcou (say that three times fast) and Frenchman Louis du Pont du Chambon (m. 1709 Port Royal).

Jacques’s parents were Canadian Maurice Vigneau and Acadian Marguerite Comeau (m. about 1701 in Port Royal).

After several forays into their genealogies, I can find a slant kinship between Jacques and Joseph Brossart through Jacques’s first wife Marguerite Arsenau. Marguerite and Brossart were second cousins; their maternal grandmothers were sisters (Anne and Madeleine Blanchard). But Murdoch didn’t comment that Jacques and Joseph were kinsmen.

Did Vergor and Jacques have closer family ties?

I can’t find a cousinage between the Vigneaus/Comeaus and the Mius/ d’Entremont families. The closest tie seems through godparents.

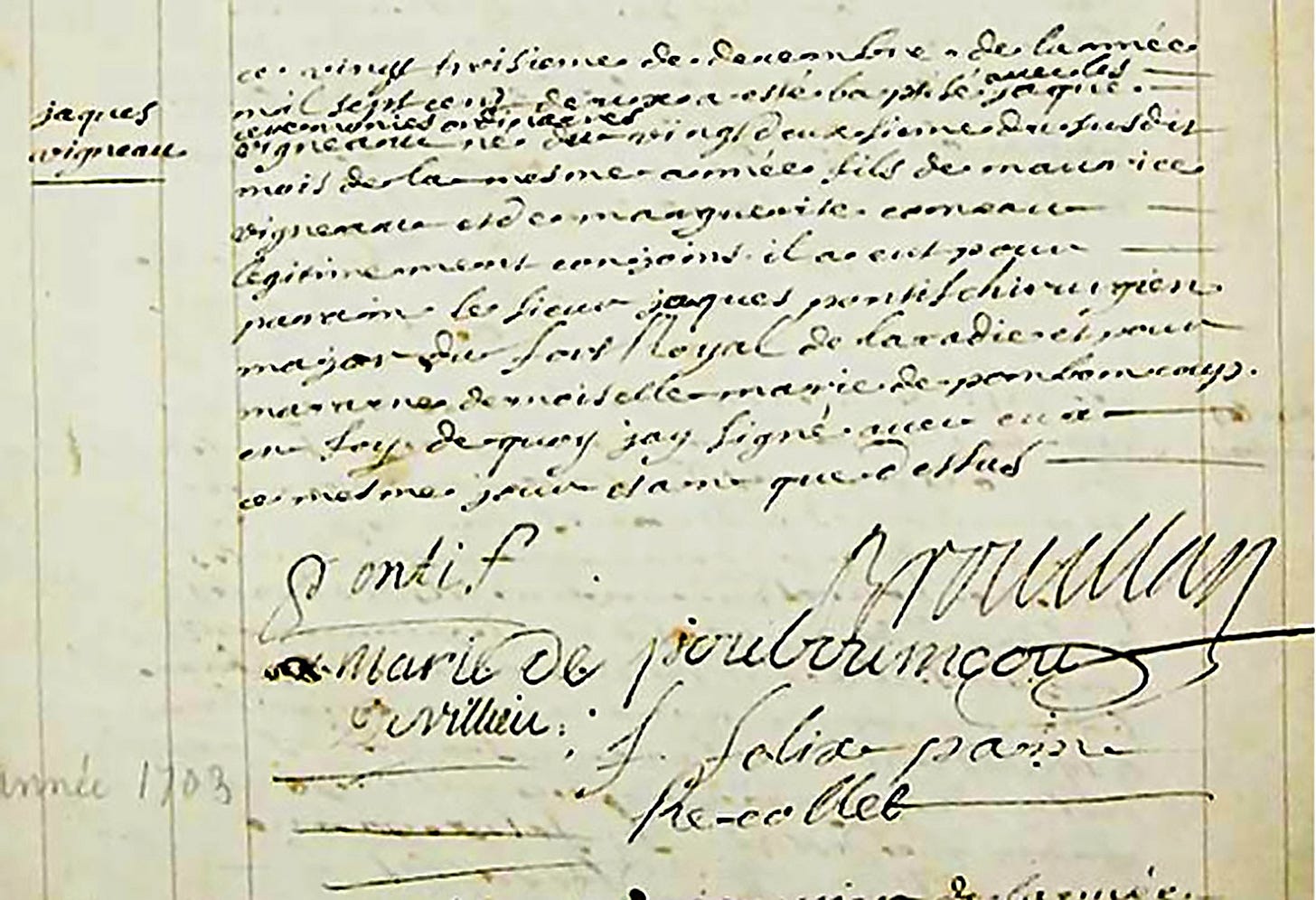

Jacques’s godmother was Demoiselle Marie de Pouboumcou.* His godfather was Sieur Jacques Pontif, surgeon major of Fort Royal.

They sound like local elite, this demoiselle and this sieur.

Jacques Vigneau baptism from Parish registers of St-Jean-Baptiste de Port-Royal, Acadie. Provincial Archives of Nova Scotia, Canada.

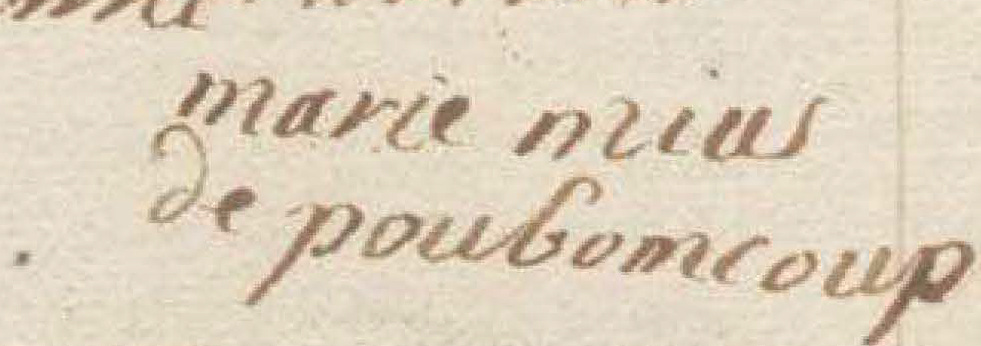

It’s possible the Marie de Poubomcou who was Jacques’s godmother was Vergor’s maternal aunt, his mother’s older sister Marie (b 1684, m. January 1705 in Port Royal). Though I’m no handwriting expert, the signature on Marie Mius D’Entremont’s marriage certificate looks similar to the signature on Jacques’s baptismal certificate, especially the “d” and the “r”:

from François Dupont du Vivier and Marie Mius de Pobomkou marriage 12 January 1705

Jacques’s godfather Sieur Pontif is actually Jacques David, who was born in Château-Richer, Canada, Nouvelle France. Pontif was “the garrison surgeon, responsible for shaving the soldiers and looking after their medical needs. Pontif built three houses on his large property. One house, equipped with a billiard table, seems to have operated as a public billiard hall and tavern. Another served as a garrison hospital until one was constructed on the glacis of the new fort” (Dunn, p. 58).

Not that I wouldn’t want a godfather who ran a tavern and billiard hall, with a nearby hospital, or a godmother whose family was a political and social force, but why didn’t Jacques’s parents pull in at least one of the Comeau relatives for him?

In 1702, Marguerite Comeau had two brothers and three sisters who were at least 16. When Jacques’s brother (Marie Vigneau’s father) Jean Baptiste was born 14 years later, they’d picked Jean Comeau and Marguerite Pitre, wife of Abraham Comeau as parrain (godfather) and marrain (godmother).

Did godparents mean something different for first-born Jacques? Did becoming a godparent in 1702 Port Royal, Nova Scotia, make unrelated families kin?

Out of my wheelhouse and unable to resist the pull of the genealogical rabbit hole, I decided to “Ask a historian.”

My go-to is Patrick Lacroix, Director of the Acadian Archives. Dr. Lacroix sent three references. “The articles insist on the importance of ‘godparenthood’ in establishing social ties where a blood relation was non-existent. But... the one from Acadiensis highlights the intensity of blood relations in a ‘large’ community like Port-Royal.”

Early 1700s, Port Royal was not the hub of endogamy it would become by the deportation years. About half the spouses, mostly the husbands, were born outside of Acadie:

“The parish register of St. Jean Baptiste shows that in almost every second marriage in Port Royal between 1702 and 1714 one of the partners, usually the husband, had been born outside the settlement. Although some of these came from neighbouring Acadian villages, and some from Canada or Cape Breton, the majority immigrated from France.” (Hynes, p. 4)

Still, in 1702, there were blood relatives available to Jacques’s parents, so something more than family ties went into Maurice’s and Marguerite’s selection.

Maurice, a sailor-carpenter, was a recent emigré from Île d'Orléans, having arrived in Port Royal from Canada just two years before Jacques’s birth. He was a master carpenter helping to restore the fort at Port Royal. Pontif was surgeon major for the garrison. Marie de Pouboumcoup’s** father was a co-seigneur of Port Royal. They likely knew each other from those roles as carpenter, doctor-barber, and landlord’s daughter.

Given what Dunn said about some of the not-Acadian husbands coming from Canada, maybe Maurice Vigneau and Jacques David had a closer cultural affinity with each other than with the French from France or Acadia.

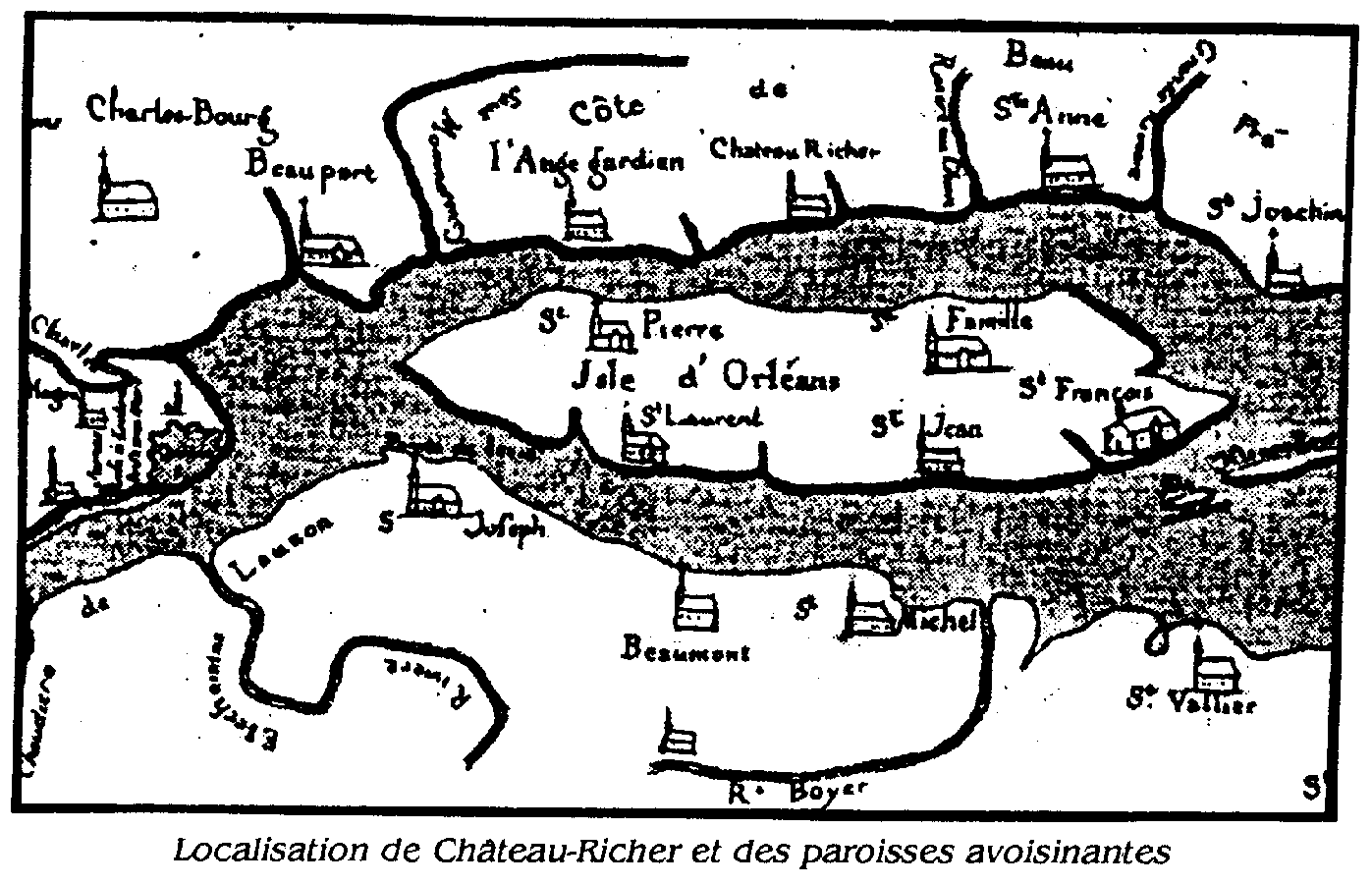

In Canada, Maurice was born in Sainte-Famille, Île d'Orléans, which was across the river from Château-Richer where Pontif was born four years before him.

https://marinboucher.blogspot.com/2006/05/chteau-richer-1650.html

Maybe their shared Canadian mainland roots, and their not-from-Acadia status brought them together as well as their time at the fort and in town.

Maybe Jacques’s parents were establishing social ties with the Mius d’Entremont family.

Maybe the French Catholic mindset about the seriousness with which one took godparenthood was alive and well:

“…godparents became relations of both their godchildren and their godchildren's parents, by means of spiritual kinship.” (p. 486, Alfani et al).

If this is so, then the kinsmen relationship between Jacques Vigneau and Vergor was forged through a spiritual link that expanded the definition of family. His baptism may have allied Vigneau and Comeau with Mius d’Entremont and Pontif.

Reminds me of the bonds that form with sister-friends, adopted children and their parents, and step-parents and step-children.

Between Jacques’s baptism in 1702 Port Royal and the Grand Dérangement of 1755 when he was deported from Baie Verte, a lot of life happened. But life events and the upheavals of war didn’t erase family ties. Bonds were significant enough for Murdoch to note in 1865 that Jacques was said to be a kinsman of Vergor.

Modified from a chart sent by my brother John (thank you!)

Something fun — Walking tour of Annapolis Royal 1710

The Annapolis Heritage Society created a map of homes in 1710 Port Royal. The Vigneaus are at #29 and the Pontifs at #23. Jacques’s maternal aunt Madeleine Comeau is at #25. His mother’s cousin Anne Comeau is at #35.

I imagine an 8-year-old Jacques on his own walking tour of family homes.

Source: Acadian Walking Tour Map produced by Annapolis Heritage Society https://annapolisheritagesociety.com/

Note

* Poubomcoup is the place Mi’kmaq considered a place where in winter you can go fishing for eels in the port by digging holes in the ice. Today it’s Pubnico.

** Marie (de Pobomcoup) Mius D'Entremont may have a tale worth telling. The Acadian WikiTree entry for her says The marriage created somewhat of a scandal within the French Colonial military as it was performed in secrecy by Felix Pain, the garrison chaplain, against the wishes of the acting Governor. About three months after her wedding, she gave birth to her first-born.

Thank yous -

because looking for the scattered traces to reconstruct the invisible history takes a village

Sally Buffington who, after she read my first Acadian Bits and Pieces, shared the Emily Dickson poem about telling the truth slant.

Ralph Geer for finding out that Sieur Jacques Pontif is Jacques David on WikiTree

Lois C. Jenkins, Researcher, Annapolis Heritage Society for finding Pontif in Brenda Dunn’s book on the history of Port Royal

Dr. Patrick Lacroix, historian, Director of the Acadian Archives at the University of Maine Fort Kent for answering any and all questions Acadian — and even some that are not

Lisa Maguire, historian and Substacker, for ways in which to use microhistory tools in family storytelling

The volunteers who make the Acadian WikiTree such an invaluable resource.

Resources

Alfani, Guido, Agnese Vitali and Vincent Gourdon. 2012. Social Customs and Demographic Change: The Case of Godparenthood in Catholic Europe. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion, SEPTEMBER, Vol. 51, No. 3, pp. 482-504; https://www.jstor.org/stable/41681807

Berteau, Camille, Vincent Gourdon and Isabelle Robin-Romero. 2012. Godparenthood: driving local solidarity in Northern France in the Early Modern Era. The example of Aubervilliers families in the sixteenth–eighteenth centuries, The History of the Family, 17:4, 452-467, DOI: 10.1080/1081602X.2012.752758

Dunn, Brenda. 2004 A history of Port Royal/Annapolis Royal, 1605-1800. Halifax, N.S. : Nimbus Publishing.

Hynes, G. I. (1973). Some Aspects of the Demography of Port Royal, 1650-1755. Acadiensis, 3(1), 3–17.

Murdoch, Beamish. 1865. A history of Nova-Scotia, or, Acadie. Halifax NS: J Barnes. https://archive.org/details/ahistorynovasco01murdgoog p. 273

Ann, you are a wonderful storyteller. You are an expert at connecting the dots. I love your stories.

I think I intuitively follow your advice on family story writing. For example an ice scoop provided an introduction to a profile of a great uncle, with an aside to his father (owner of the scoop), vague personal memories and census and news clipping research. I also visited the town where he lived and tried to reconstruct where he lived. It was enough for a story and contained a mystery - Why did he not enlist during WW1 when his three younger brothers did? That said, he remains an enigma.