"When a community loses its memory, its members no longer know one another. How can they know one another if they have forgotten or have never learned one another's stories?"

Berry, Wendell. What Are People For? 1990. California: Northpoint Press Albany. posted on https://www.eplhstory.ca/

It’s a sobering moment to come across a bit of history in which the ancestors of our traumatized and deported Acadian ancestors participated in traumatizing and deporting others.

There they are in 1696 on Newfoundland’s Avalon peninsula — “…Canadians, Indians, and Acadian adventurers…” about to wipe out English fishing villages. (see For More Information, Williams, p. 34)

The question arises: “what the hell is going on with people?”

The answer comes with a frisson, a shiver, a pause, a shift in knowing. Something to explore, to reflect upon, to confront.

This moment began with a trace up an Acadian Bourgeois branch, from my great-great-grandmother (Angele Bourgeois) to an English name in my genealogy shrub: William James.

How did he, an English youth in late 1600s Newfoundland, become a French ancestor in early 1700s Montreal?

D’Iberville. A home-grown military icon of Canadian history.

Pierre LeMoyne d’Iberville, who history credits with founding the colony of Louisiana.

But before he went south, he went north. At his own expense, he brought along the Canadian, Indian, and Acadian adventurers.

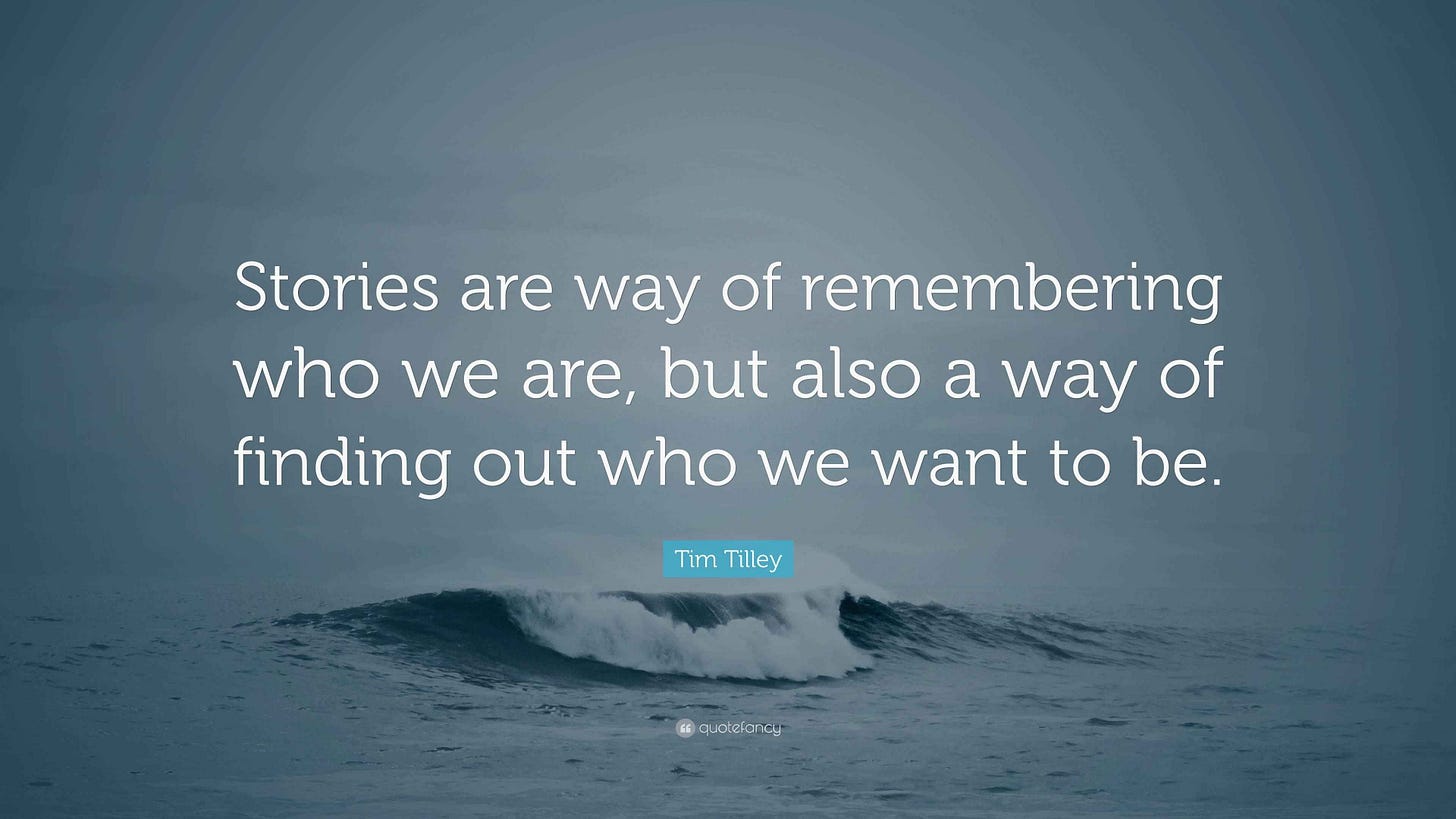

The particular genealogical moment for William James, the moment that changed him from English Episcopalian to French Catholic, began with d’Iberville’s 1696-7 raids on the Avalon Peninsula in Newfoundland. The raiders — Canadian, Acadian, Mi’kmaq, and Abenaki — decimated 23 English villages.

William was a 14 year-old lad living on the shores of Conception Bay in one of them.

The other ancestors were not the good guys in this episode.

View of the Colony of Avalon NHS (© Parks Canada | Parcs Canada)

Why would they do that?

Payback and trade wars.

In 1688, over in Europe, France to be precise, Louis XIV started a war to expand his territorial and dynastic claims: the War of the Grand Alliance. Catholic and Protestant conflicts were high. The Bourbon and Habsburgs each itched to take control over Spanish possessions when epileptic and half-mad Charles II died.

It was yet another reason for cousins, whether they remembered their ancestry or not, to wail on each other for power and resources.

In Newfoundland, the French lived in Plaisance, and the English in the other island villages.

They were there to fish.

https://recherche-collection-search.bac-lac.gc.ca/eng/home/record?idnumber=2926914&app=fonandcol&ecopy=c003686

And to skirmish with each other, as they had for decades, on behalf of their monarchs, to control the fisheries.

One of the first significant conflicts occurred on February 25th, 1690, when Plaisance was attacked by an English party of privateers, mostly composed of Ferryland residents. Arriving by sea, the English took the community by force, killing at least two soldiers and imprisoning members of the community inside the local church for approximately six weeks as they looted and ransacked the town. (1)

— If history were a novel, this would foreshadow events in 1755 at Grand-Pré, Nova Scotia, when the British locked the Acadian French in a church before pillaging and burning that community, then deporting the villagers. —

Back on the Avalon Peninsula, after 1690, there were a few more back-and-forths between the English and the French, until in 1696-7 French leaders D’Iberville and de Brouillan led a campaign by land and sea against the English villages. They wiped out 23 English settlements from November 1696 to February 1697.*

Nicolas Langlois (1697). “The sacking of English settlements in Newfoundland in 1696 by the French. War of the Augsbourg.” Credit: Gallica / Wikimedia Commons. License: public domain.

After capitulation, Ferryland’s residents stood by helplessly and watched as the “enemy […] burnt all our houses, household goods, fish, oil, train vats, stages, boats, nets and all our fishing craft […]” (1)

— If history were a novel, this would foreshadow events at Beaubassin, NS in 1755 when my Bourgeois and Vigneault ancestors, among the many Acadian families there, watched their homes burned and pillaged before they were deported to the British colonies on the now eastern U.S. seaboard. —

pngtree.com

The story begins to have the feel of a dual timeline historical novel.

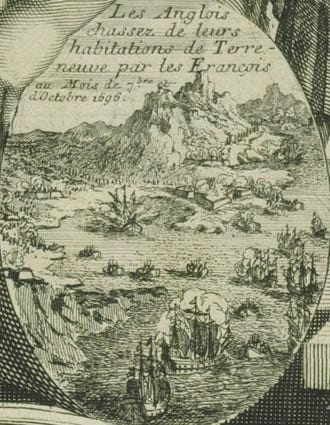

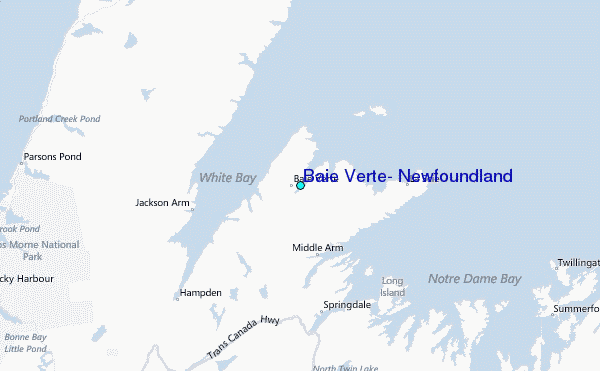

In William James’s genealogical transition moment, when he lived in Bay Verde, NF, he may have been the new boy in the neighborhood. His Catholic baptism record says IL A ETE ENVOYE VERS LA FIN DE L'ETE 1696 A BAIE-VERTE, ILE DE TERRE-NEUVE. Translated: He came to Green Bay, Newfoundland at end of summer 1696.

At age 14, was he old enough that he was there without his parents? Did they die in the skirmishes? Did they return to England?

Of all the unlucky times to find yourself in a new place

tide-forecast.com

William was captured by French soldier Claude Robillard in January, 1697. “Pris à la Baie Verte, Terre-Neuve en janvier 1697 par Claude Robillard, soldat, d'Iberville.” https://www.nosorigines.qc.ca/GenealogieQuebec.aspx?genealogie=James_William&pid=26605

Had William come to know his neighbors in the four or so months between the end of summer 1696 and his capture in 1697?

Abbé Baudoin’s 1697 journal noted that "there were in this harbour fourteen settlers well established and ninety good men" https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Bay_de_Verde

And probably an iceberg or two. It was winter in Newfoundland.

ehcanadatravel.com

Many of the English settlers caught up in d’Iberville’s Avalon Peninsula campaign were sent on ships back to England.

Why was William, instead, brought to Montreal? And who were the other prisoners and where did they go?

In 1698 Montreal, he was a pensioner with Sulpician priest Léonard Chaigneau when he was baptized into the Catholic faith. Robillard, a master butcher (2), was one of his witnesses.

From the Catholic baptism record, we know that William, was born in Pimperne, Dorset, England on Dec. 27, 1682.

https://www.opcdorset.org/Pimperne/Pimperne.htm

In Montreal, he became Guillaume Langlais (William English). Or Jacques Sansoucy. Or Guillaume Jacques. Someone on nosorigines decided to settle it with Guillaume Langlais-Sansoucy-Jacques.

In 1703, William married Catherine Limousin de Beaufort, who has her own backstory worth exploring someday. She was said to have “plusieurs amants” (many lovers) and to have been 7-months pregnant when she married William. Her child, and two others before this one, died.

That’s at least curious, and I sincerely hope not nefarious, given that Catherine and William had six living children.

Were William and Catherine two lost souls living on the margins of their communities, two souls who happened to find solace in each other? Who recognized trauma when they saw it, even if they had no idea what it was called?

Some of their offspring married into both Acadian and English refugee families(3) : Littlefield tracing to Wells, Maine, Stebbins tracing to Deerfield, Massachusetts, and Bourgeois tracing to Beaubassin, Nova Scotia.

They wove ancestral stories of French and English victims at the hands of English and French oppressors. Their heritage — my heritage — became a bit more complicated through them.

I begin to wonder, is there a gene, or an epigenetic change that renders one more inclined to recognize other refugees, a sort of radar for detecting the trauma and uprooting that makes one a refugee rather than a migrant?

Because they weren’t migrants in the sense of willing emigrants or immigrants, seeking fortune, escape, or adventure. They were forced out of where they’d known into places where they eventually adapted, and, I hope, came to love or at least find peace.

Without William James at the tip of a genealogy branch, the Avalon campaign in Newfoundland would have remained for me another historical incident in the interminable military encounters that populate recorded documents. You know, the ones that make your eyes glaze over and your brain turn to pudding.

I wonder: Who in the now, in our global conflicts about trade, is the William James to a future generation? Whose story needs to be remembered?

letterpile.com

* I wondered about the wisdom of a late fall to early winter campaign that far north. Seems Bay Verde has an average temperature range of 25-degrees Fahrenheit in winter and 60-degrees Fahrenheit in summer. Cold but manageable — as long as the snow doesn’t fall or the ice forms.

Thank you to Donna Doucette, Library Assistant VIII, Centre for Newfoundland Studies, QEII Library, Memorial University of Newfoundland and Labrador for help in locating information.

Sources

(1) A casualty of the 1696 French attack on Ferryland, Newfoundland By Eric Tourigny

(2) ENGLISH CAPTIVES & PRISONERS REMAINING IN NEW FRANCE by Roger Lawrence, AMERICAN-CANADIAN GENEALOGICAL SOCIETY, MANCHESTER, NEW HAMPSHIRE 2015, p. 171. Available at: https://acgs.org/product/english-captives-prisoners-remaining-in-new-france-2nd-edition/

(3) William and Catherine’s daughter Marguerite James dit Sansoucy married Deerfield captive Joseph Stebenne’s in 1734 Fort Chambly. Joseph’s sister Thankful-Louise-Therese, also a Deerfield captive, married militia captain Adrian-Charles Legrain (dit Lavallee) in 1711 Boucherville. Thankful and Adrian are also my ancestors.

In 1753, William and Catherine’s granddaughter Marie Parent married Francois Letrefils, son of English refugee Aaron Littlefield. Aaron Littlefield was kidnapped during the Northeast Coast campaign of 1703 during a raid led by Alexandre Leneuf de La Vallière de Beaubassin. (Marie and Francois are my ancestors)

Leneuf’s family seigneurie in Beaubassin had been raided in 1696 by New England military forces (les Bostonnais), a raid reported to be in retaliation for a French raid on Pemaquid (Bristol, Maine). D’Iberville was at Pemaquid before heading up to Newfoundland.

And, weaving the thread back into Acadie, Francois and Marie’s daughter Archanges married Francois Bourgeois in 1814 in St. Antoine-sur-Richelieu, Vercheres. Francois is the son and grandson of Acadians booted out of Beaubassin during the Grand Dérangement.

Francois’s Acadian grandfather Pierre was brother to Claude Bourgeois, husband of Marie Vigneault, the ancestor whose story is the kernel of my historical novel-in-process.

One more thread to the tapestry of interconnections — d’Iberville was the nephew of my ancestor Anne Lemoine. She and his father were siblings. He is my first cousin 9 times removed.

For more information

Before the French and English, Basque fishermen in Newfoundland

Colony of Avalon, National Historic Site of Canada

Colony of Avalon planned as a utopia

Calvert chose the name for his new property himself. “Avalon” evokes a couple of English legends. In one, “Avalon” refers to a place of sanctuary located in Somerset, England where Christianity is said to have been first received in its more or less unified, pre-Reformation configuration. In another, Avalon is an island, a refuge, where King Arthur and his knights went to be healed. Perhaps it’s within the bounds of possibility that the name choice indicates Calvert’s desire for an enlightened, peaceful place where Anglicans and Catholics could live harmoniously side-by-side even if their faiths remained unreconciled.

Father Baudoin's War: D'Iberville's Campaigns in Acadia and Newfoundland 1696, 1697 by Alan F.Williams. 1987, Memorial University of Newfoundland

This book is hard to find, but your local librarian can work miracles and borrow a copy for you. Chock full of intrigue, petty squabbles, and the horrors of war on civilians, the so-called normal consequences of war. Hard to this modern eye to read about massacres and adventures in the same paragraph without needing an anti-nausea aid.

This was really interesting to learn. I know nothing about the history of Newfoundland, and you have motivated me to find out more.

This is one of your most interesting so far, Ann. Fine work! "Tangled webs" seems a major understatement.