Deciphering Acadia

You can't believe everything you think

statesymbolsusa.org

If you’re a reader in the U.S., do you remember learning about Casimir Pulaski in your U.S. history courses?

I don’t.

Casimir’s name came up a few weeks ago in a lively discussion with somehow-Acadian cousin Savanna King in Louisiana about not-Expulsion Acadians who may have traveled the Atlantic Ocean from Cape Breton to France to St. Domingue (Haiti) to Georgia and New Orleans.

I only knew Casimir’s name because when we were kids we’d pass Casimir Pulaski State Park on our trips from Southbridge MA to Point Judith RI.

waynebarbersoutdoorscene.blogspot.com

So I Googled Casimir.

Turns out Casimir, the Father of the American cavalry, saved George Washington’s life. We may not have celebrated Washington as our first President without Casimir.

Turns out Casimir was an immigrant.

Turns out Casimir was an intersex person.

So much for the current screaming in some U.S. political circles that non-binary folk don’t belong in the military. There are a lot of parks, monuments, and roadways honoring Casimir’s prominent role in the American Revolution.

You can’t believe everything you think.

I passed the story along on Facebook where a friend suggested that maybe it would be a good idea to collect these sorts of stories before they are erased from U.S. history.

Like stories of Acadians?

Yes, I’m still a little bitter. So, remembering Yvon Labbé's advice, perhaps it’s time to squeeze that lemon. Time to dig into my abundance of Acadian books, papers, and journals, most collected these past two years from out-of-the-way places.

Ironically, I recovered, a 2012 book titled Acadia Lost by A.M. Hodge.

Cousin George Comeaux gifted it to me in 2012 when he met the author at a July 22 book fair at the John Winslow house in Marshfield MA. Yes, Winslow of Acadian Deportation notoriety. Irony noted.

George included a note about the Acadian talks held at the end of the day. Most visitors had left. Those who stayed comprised a small group of Acadians and Acadian-adjacents telling their stories to each other. Irony upon irony.

Before I began to read the novel, my idea of Acadia, after the Treaty of Utrecht (1713) until the Grand Dérangement (1755), was that it was a land of peaceful, well-fed, fecund farm families and roguish sailor-traders, whose extended family included Mi’kmaq kin. They spent a lot of time building and fixing dykes, collecting apples, and learning about how they were related to each other so that they didn’t marry too close a cousin.

I imagined the occasional outbreak of nonsense and dispute because, even when you are related somehow to most people you encounter, there’s no guarantee you’re going to get along with or even like your relatives.

I saw our ancestors as tolerant of French and English claims to their lands (much claimed from the sea rather than stolen from local inhabitants), while not taking claims all that seriously because one never knew when either country was going to claim to be the government of record.

Then I read Hodge’s end notes.

You can’t believe everything you think.

She mentioned Gorham’s Rangers (1744) and their raids of terror in Acadia.

Raids of terror? Eleven years before the Expulsion?

Sure, there had to be British and French soldiers traveling hither and yon about the countryside because that’s what soldiers do on behalf of their sovereigns. But I had this picture of them staying out of each other’s way for the most part, and of Acadians offering a meal to whomever. Because offering meals seems to be built into the Acadian genome.

https://tourismnewbrunswick.ca/story/9-acadian-foods-you-have-to-try-in-new-brunswick

You can’t believe everything you think.

O my, my. John Gorham was a Yarmouth, Cape Cod militia man who led a company of Cape Cod Wampanoags and Nausets on missions and raids to protect British interests, mainly the garrison at Annapolis Royal. And whatever else the British were interested in along Bay of Fundy shores.

Seems he learned tactics from Benjamin Church (1639-1718), a New England colonial officer, who Americans tout as the Father of the Rangers. Acadians tend to see him differently. I wonder how today’s Wamapnoag see him since he’s responsible for killing the sachem Metacomet.

You can’t believe everything you think.

In “Savages” in the Service of Empire: Native American Soldiers in Gorham's Rangers, 1744–1762, historian Brian D. Carroll says

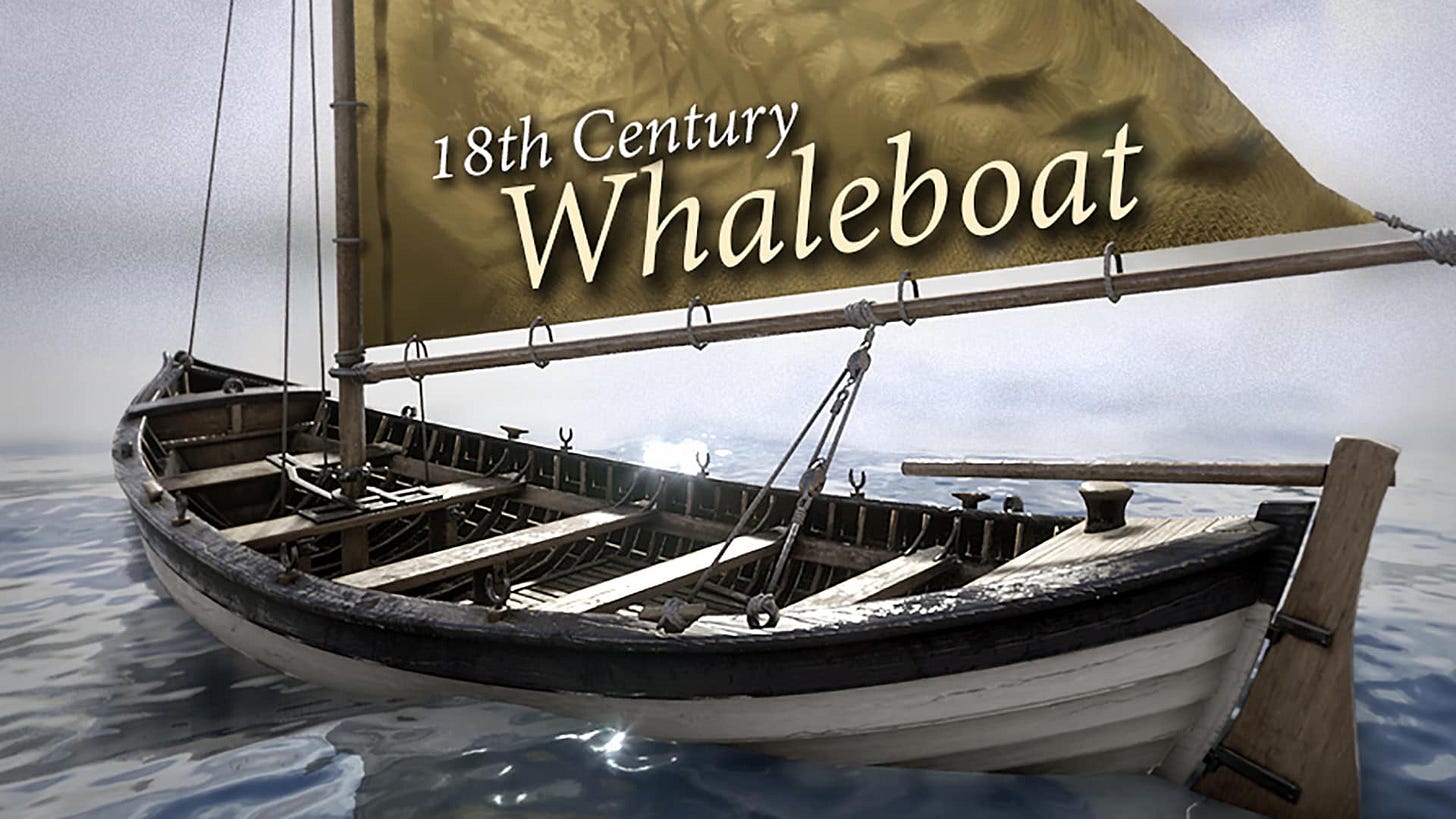

“GORHAM’S RANGERS, formed in 1744 as an auxiliary unit of the Massachusetts provincial army, was an amphibious strike force that patrolled the coasts, inlets, bays, and rivers of the Canadian Maritimes in modified whaleboats.”

unrealengine.com

Why would indigenous men join conquerors to protect other conquerors? And from whom were they protecting them? What did they have against Acadians and Mi’kmaq?

The Historical Society of Old Yarmouth (Massachusetts) website has a partial answer:

“Overseer accounts indicate that Gorham’s call to arms had strong appeal for these men, since it played to their martial traditions. In addition, one third were in debt, and another third were indentured servants, both conditions inclining them to recruitment. There was also a promise of extra pay from bounty money, typically a reward for enemy kills and captures in frontier campaigns.”

If that’s true, then the indigenous men were mercenaries killing and capturing Acadians and Mi’kmaq on behalf of the Brits.

What about the French? Seems the Brits might have more of a problem with the French. It was their monarchs who engaged them in repeated cold and hot wars, wars that originated from extended family squabbles about who owned what through hundreds of years.

Was there a more going on among Acadians during the Golden Age than building dykes and aboiteaux, raising cattle, and trading? Weren’t Acadians famous for neutrality?

pixy.org

Was there an Acadian militia or army that’s somehow disappeared from the story? Was this a matter of conflating Acadians with French soldiers? Were there Acadians who were anything but peaceful, neutral farmers and traders?

I think the answer is “it’s complicated.”

By 1744, when Gorham formed his Rangers, Acadia was full of children, sort of like the Baby Boomer horde after World War II. If you have doubts, notice how many children and babies were on the deportation ships out of Port Royal in 1755 (see Acadian Odyssey, in which those deported from Port Royal are enumerated).

I wondered, “Were they really terrorizing a largely youth-based population?”

“Gorham’s strategy to subdue local resistance included subterfuge, “skulking,” surprise attacks, and terror against enemy noncombatants, including taking captives (some used as hostages, some killed, and a few sold for servants in New England), and killing and scalping Mi’kmaq women and children. (p. 396, Carroll)”

Terror against enemy noncombatants.

Killing and scalping Mi’kmaq women and children.

Well THAT certainly did not come up in my U.S. history classes.

“The scalp bounties were not only a potent recognition of Indians’ war prowess; they were for many rangers and their families the only money they would receive for their service.” (p. 406, Carroll)

Paid for scalps. THAT’s the bounty the Old Yarmouth Historical Society means by “promise of extra pay from bounty money, typically a reward for enemy kills and captures in frontier campaigns.”

Even if you say “standards were different then,” it’s still creepy. Still terrifying. Still requires a person to engage in mental acrobatics to feel okay about doing that to children so that you can have an income.

You can’t believe everything you think.

Or feel as the case may be.

It’s one thing to read about these military conflicts and believe they were one-and-done, or that a Klingon-style glory was achieved from battle, or that combatants incurred no moral injury, or that non-combatants incurred no generational trauma.

It’s quite another to imagine yourself standing on a shore looking out over relatives who were terrorized and scalped.

This, too, is part of history.

The image that emerges for me now of this period of Acadia is of a more anxious time for our ancestors. I wonder whether some part of the community stood lookout for those modified whaleboats, whether some hamlets and villages were safer than others, whether a squirrel gun was adequate protection.

I have more admiration, too, for those trying to live peaceful neutral lives while surrounded by the threat of bloody skirmishes.

Next time I’m in Mashpee, I’ll have to stop at the Wampanoag Indian Museum and learn their version of the raids on Acadia. I wonder: do they even know? How do they tell this part of their history that intertwines with ours?

mashpeewampanoagtribe-nsn.gov

For more information

Gorham's Rangers - the forerunners of the US Army Rangers

Colonel John Gorham’s Account Book

Ordinary Men by historian Christopher R. Browning about ordinary men enlisted in an auxiliary police force that terrorized and murdered Jews in World War II. Netflix made a documentary of it telling this story through the eyes of the perpetrators.

It is definitely complicated! 😅 But so very interesting.

Just returning to this post after a couple of months of assimilation with my only recently rootsing around my ancestry.

I rate this as another super-encyclopedic blending of your source and themes into a genealogical gumbo of mysterical interactions among the human species!

I am picturing myself signing the neutrality declaration, then thirty years downstream being sanctioned because then generation that followed did not adhere to my pledge. My own life experience tells me, my offspring would scoff and say "that was your life __ we didn't pledge anything."

As with the American natives, whose elders frequently foresaw calamaties arising and accepted uncomfortable compromises, to be mocked as "old women" by the young lions who didn't accept deliberate mistreatment and had much to prove -- my offspring consider my lifestyle an antiquity.

A while back I organized a mishmash Acadiana reading among Massachusetts Acadian David Surette, a Cajun deportee (me, proudly spouting the X surname appendage), and non-Acadian A.M. Hodge, who dove into the culture based on an intense sensation she felt when visiting our homeland. Her novel followed three fictional brothers as soldiers of fortune, one marrying in the community, one into the Mik'maq culture, and one into the Massachusetts commerce culture. How could anything hold still with those tributaries?

Then David Surette suggested a book (I can't remember the title and found the details too triangular to pursue) which described constant tugs of war between related entities, with instigators of all backgrounds, shapes, and sizes. Apparently the young lions were not aware they were in the forest primeval. (I came to realize "Acadia Lost" was parallel to "Paradise Lost.")

(Wish I had attended your "economy of words" school!)

Keep digging, and writing, and educating!